Reaping the Wind on the Montana Frontier

If you had to name some famous characters from the history of the American West, who would you say? Buffalo Bill? Annie Oakley? Sitting Bull? Wyatt Earp? Geronimo? Billy the Kid? Jeremiah Johnson, maybe?

(Just kidding. As much as Robert Redford would like it if we thought Jeremiah Johnson was real, he wasn’t. The 1972 movie was still a good one, though. One of my favorite bits of dialogue from the film; Del Gue, the mountain man, says to Jeremiah, “Mother Gue never raised such a foolish child.”)

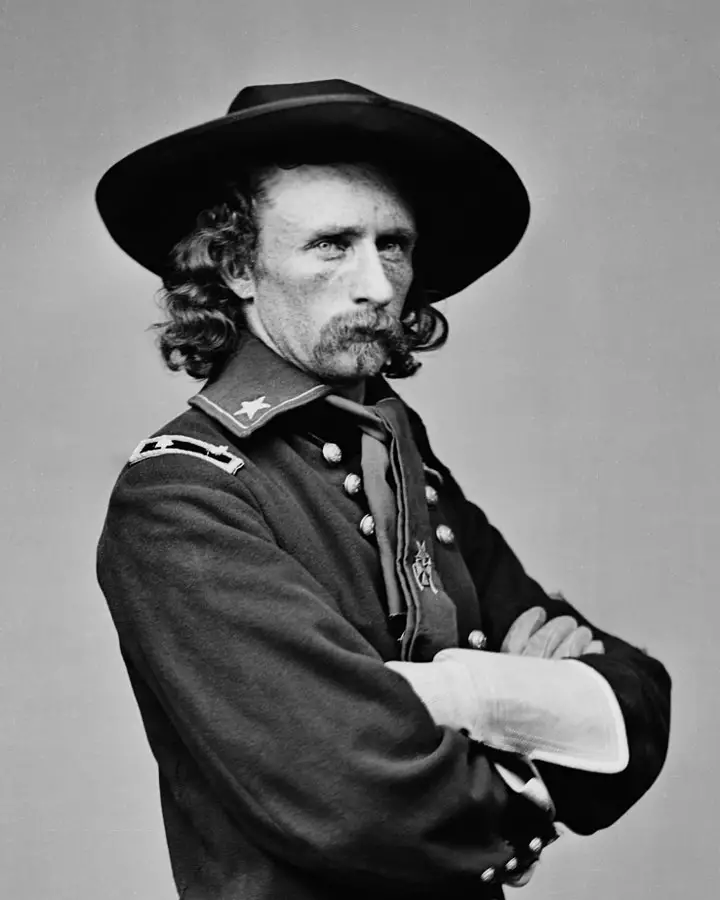

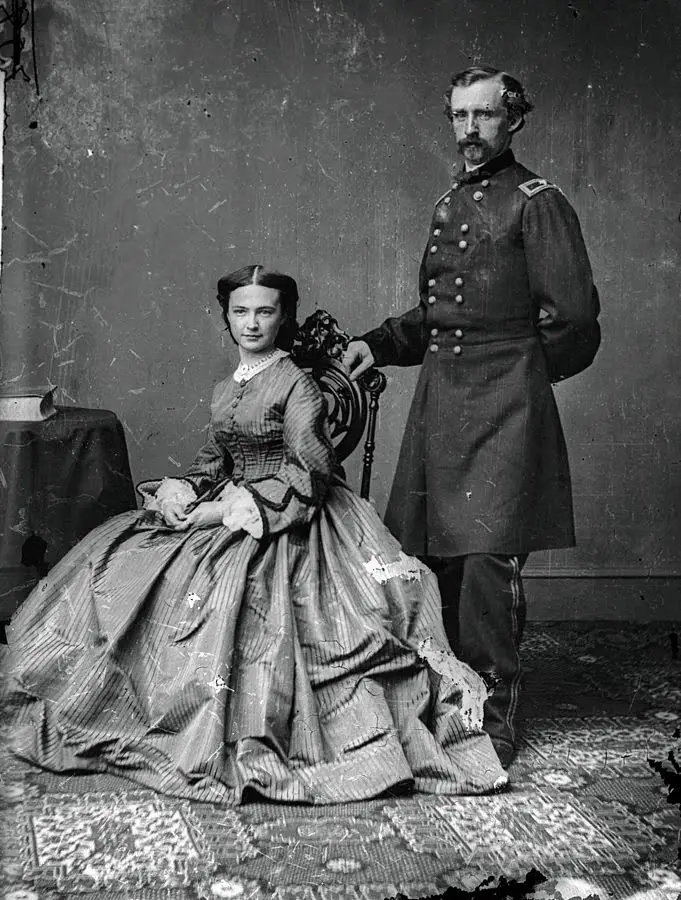

How about: George Armstrong Custer?

Brevet Major General – April 1865

Photo – US Library of Congress

If you’re a relative newcomer to American history, that name may not mean that much. On the other hand, if you been around a while, you may recognize that name as the Civil War hero that later became a general and a nationally famous Indian fighter.

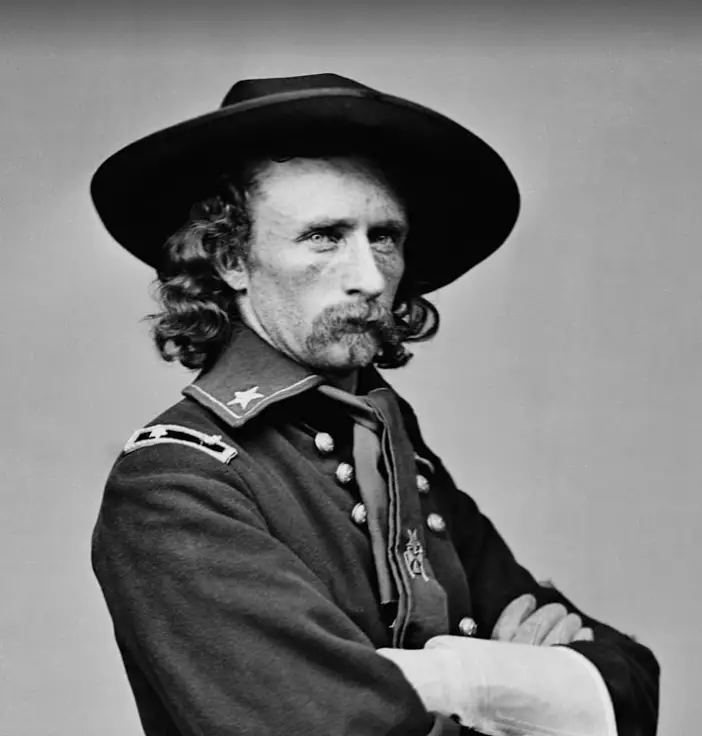

They say, “The good die young.” General Custer, or “Yellow Hair” as the indians called him, died at the young age of 36. Whether he was good or not is something that has been debated by historians and interested parties since his death on a hilly battlefield on the plains of eastern Montana in June 1876.

Custer was not from Montana. But he, quite literally, ended up there. He was born in northeastern Ohio, not far from Canton. He was raised in Michigan, south of Detroit but north of Toledo in the city of Monroe. He attended “normal” school (a teacher training academy) there before being accepted into the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

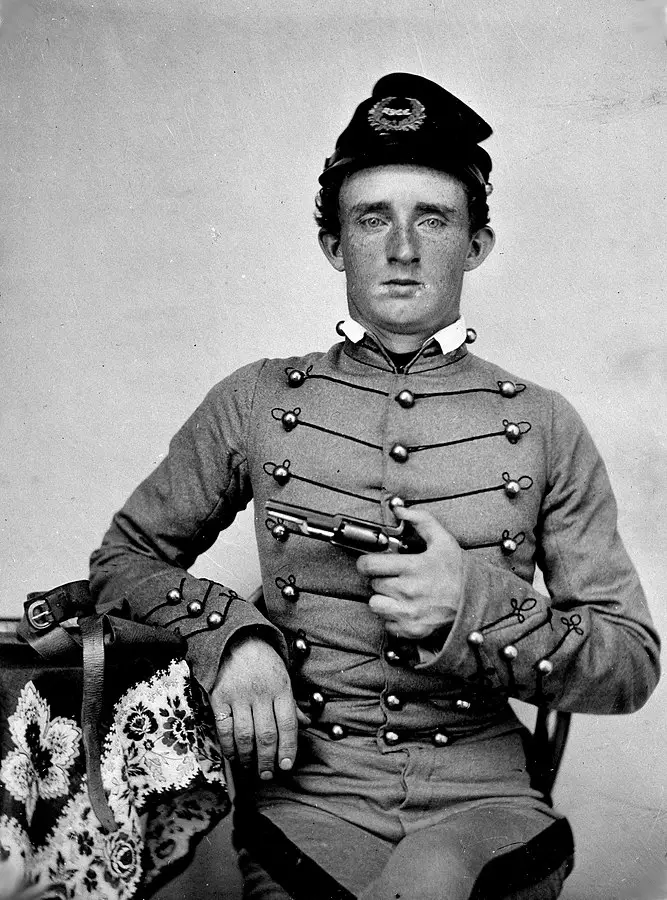

Photo – US Library of Congress

Custer didn’t do well at West Point, America’s most prestigious military academy. He was a poor student. He was disciplined a lot. During his four years at West Point he earned over 700 demerits. These are negative marks for bad behavior. To this day, Custer’s demerit total is among the worst in the history of West Point. Under normal conditions, Custer’s performance as a cadet would have earned him a poor assignment after graduation. Because the American Civil War (also known as The War Between the States) had already started, all officers were needed. He was given command of a cavalry unit as a second lieutenant and the rest, as the saying goes, is history.

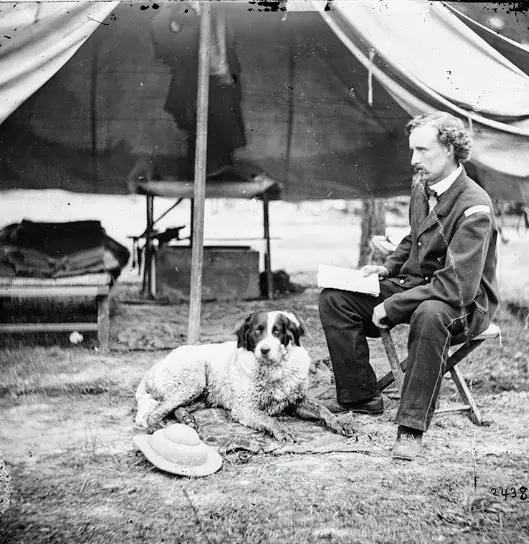

Photo – US Library of Congress

Early in the war, Custer and his unit were in the First Battle of Bull Run (in Virginia, not far from Washington, D.C.). They fought well and influenced the outcome. Custer was recognized and elevated to the staff of General George B. McClellan. He was given command of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade and was credited with some key wins in the heavy fighting at Gettysburg (Pennsylvania). Continuing his recognition on the battlefield and as a staff officer, he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. Near the end of war, he and his cavalry units fought in battles that blocked the retreat of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his army. It is estimated that Custer’s fighting helped speed up Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. That was April 1865.

Image – Bridgeman Art Library

In July 1866, Custer took command of the 7th Cavalry Regiment as a lieutenant colonel. (The ranks he achieved as Brigadier and Major General were considered wartime ranks only.) From this time forward, Custer was considered an American Indian fighter.

Photo – US Library of Congress

In 1875, the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant tried to buy the Black Hills region (what is now South Dakota) from the Sioux. Possession of the Black Hills would mean possession of the gold discovered in that area the year before.

Photo – Contributed

The Sioux refused to sell. (This was a complex matter for the Sioux. Why? Because how do you sell what you do not own? The Sioux believed the land belonged to the “Great Spirit” and they and others were only stewards, caretakers of the land.) As a result, the Grant Administration labeled the Sioux “hostiles” and ordered them to report to reservations by January 1876.

From here the dominos started to fall.

Early in 1876, the Grant Administration ordered an all-out attack on the Sioux and their allies (the Cheyenne and the Araphao). The attack was intended to be final and crushing. The attack was to be carried out by three separate but coordinated forces. One of these was led by Custer. (The others included Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen.) The plan was to surround and overwhelm the indians.

A major leader on the other side of the attack was Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Sioux medicine man and chief. He sued for peace with the United States. The U.S. Government, feeling they had a military advantage, refused.

What happened next can be accurately described as “…the fog of war.” In fact, a congressional investigation was launched in order to better understand what happened. In short, Custer’s command got too far ahead of the other groups. Custer’s force was cut off, overwhelmed, and was itself annihilated by an outnumbering force of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. There were a little over 200 men in Custer’s forces. Estimates put the opposing indian force at over 2,000. Custer tried to skirmish and fall back. He tried this several times. In the end, it was truly a….last stand.

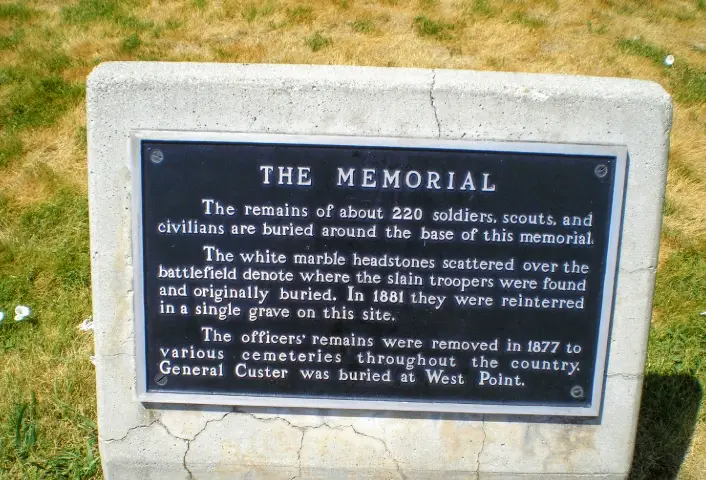

Photo – FRLambrechtsen

Monument – US 7th Cavalry – Little Bighorn, Montana

Photo – FRLambrechtsen

Photo – FRLambrechtsen

George Armstrong Custer was not originally from Montana. But his life was famously ended not far from the Little Bighorn River, an area the Sioux called “Greasy Grass,” Montana.

I have enjoyed learning about Custer. He was complex, both brilliant and flawed. I suppose that can be said of many of us. In a lot of ways, history is 20/20 vision. With Custer, this look back for me has become a cautionary tale about…hubris: a lesson learned on the beautiful rollings hills of southeastern Montana.

Photo – US Library of Congress

What struck me most in your article was: “The Sioux believed the land belonged to the “Great Spirit” and they and others were only stewards, caretakers of the land.)” Our Maori people have exactly the same opinion of their lands: they don’t own them, which led to wars here, just like the USA. And we are still trying to compensate Maori for the “theft of their lands” via our Waitangi Tribunal. See https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/

Nick….thanks for your comment. You also mentioned including more about the Sioux and their allies (the Cheyenne and the Arapaho). That’s a fair comment. Actually, there’s enough on that side of the story for a post of its own. I have that on the editorial list for the future. It’s interesting that Sitting Bull, the main “general” opposing Custer and the US Government forces, first sued for peace. That proposal was turned down because the US thought they had the military advantage. Because of this, I thought the title of this Custer post was…….apt.

Best,

– Frans

Frans, I was stupefied on the grounds of the Battle of Little Bighorn. They used to call it the Custer Battlefield but went to a more accurate name and not one celebrating the looser as it was. It is a very humbling site! Nice work. Alan*

Thanks, Alan. Glad you liked it. Linda and I felt the same when we visited the Little Bighorn battlefield a couple of years ago. We were in Yellowstone but actually felt the Little Bighorn visit was one of the top memories of that whole trip. Beautiful. Peaceful. Memorable.