Who was the woman that helped Thomas Jefferson put America on the map?

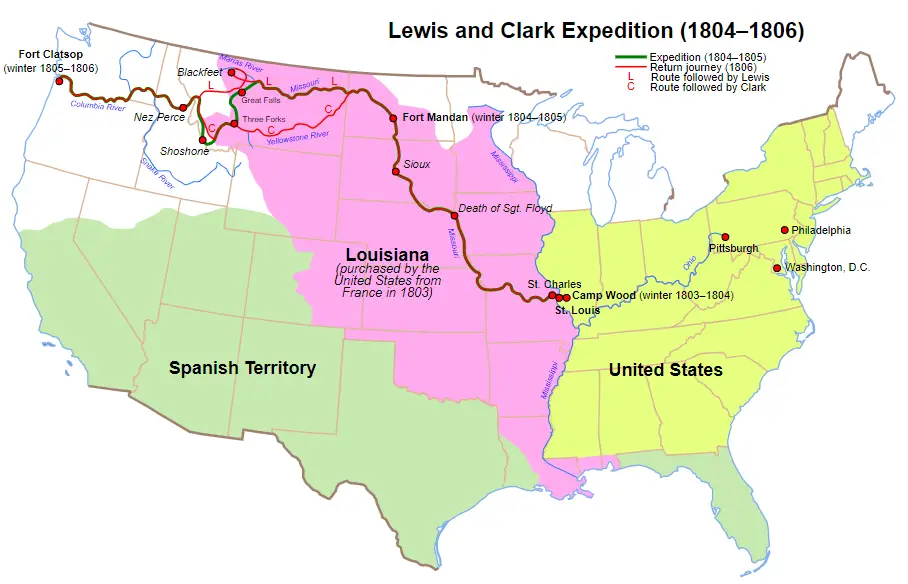

In March 1801, Thomas Jefferson became the 3rd President of the United States. At that time, the western boundary of the United States was the Mississippi River. In 1803, Napoleon and France were having trouble with their colonies in the Americas. France was also facing the possibility of war with Britain. Thinking it better to get some value for land they were considering giving up anyway, Napoleon and France offered the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States for $15 million.

Jefferson and his cabinet saw this as a very good deal. They wanted New Orleans so Americans could use the Mississippi River to trade with the rest of the world. They got that and they doubled the size of the country at the same time. (In 1803, the United States was less than 30 years old.) Jefferson wanted to know more about the land in the Louisiana Purchase. He wanted to know if there was a water route to the west coast of North America. He sent an expedition to look the area over, make maps, and to find the “Northwest Passage.”

William Morris – Portland State University

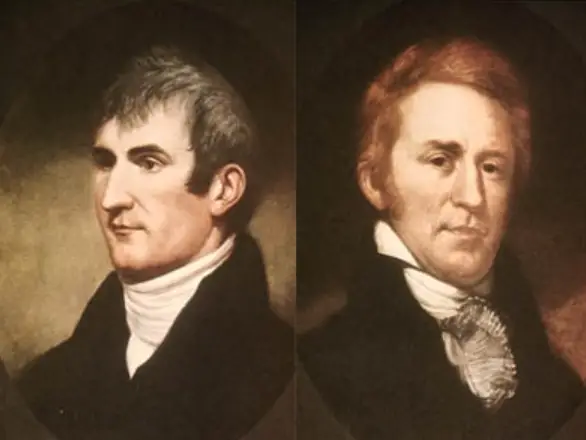

An expedition was commissioned by Jefferson. Captain Meriwether Lewis was named the leader. Lewis recruited a colleague from the military, William Clark, to join him as co-leader of the group of explorers. Their group came to be known as the Corps of Discovery.

Wikimedia

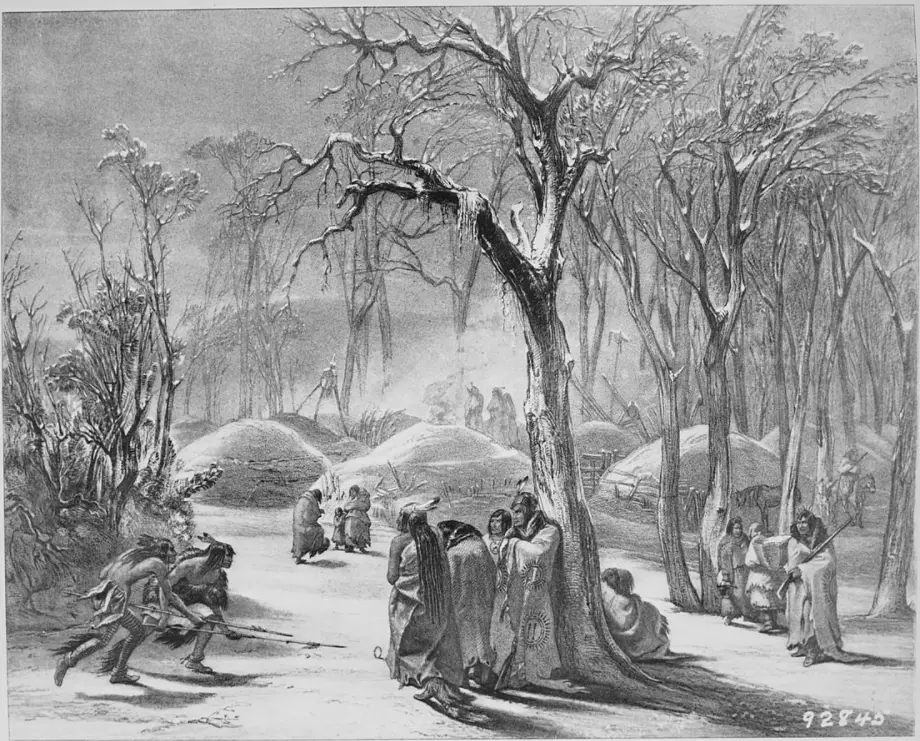

In May 1804, near what is now St. Louis, the expedition started up the Missouri River. That November, Lewis and Clark decided to spend the winter not far from present-day Bismark, North Dakota. Near their camp was a band of Hidatsa Native Americans and a French Canadian fur trapper by the name of Toussaint Charbonneau.

Karl Bodmer – US National Archives

Charbonneau had a Native American wife. She was from the Shoshone tribe. Her name was Sacagawea. She was 16 years old and was pregnant with her first child. Lewis and Clark needed a guide that could take them up the Missouri River in springtime and help them with the Shoshone people they knew they would meet near the Rocky Mountains. Lewis and Clark hired Charbonneau. They got their guide…and an interpreter.

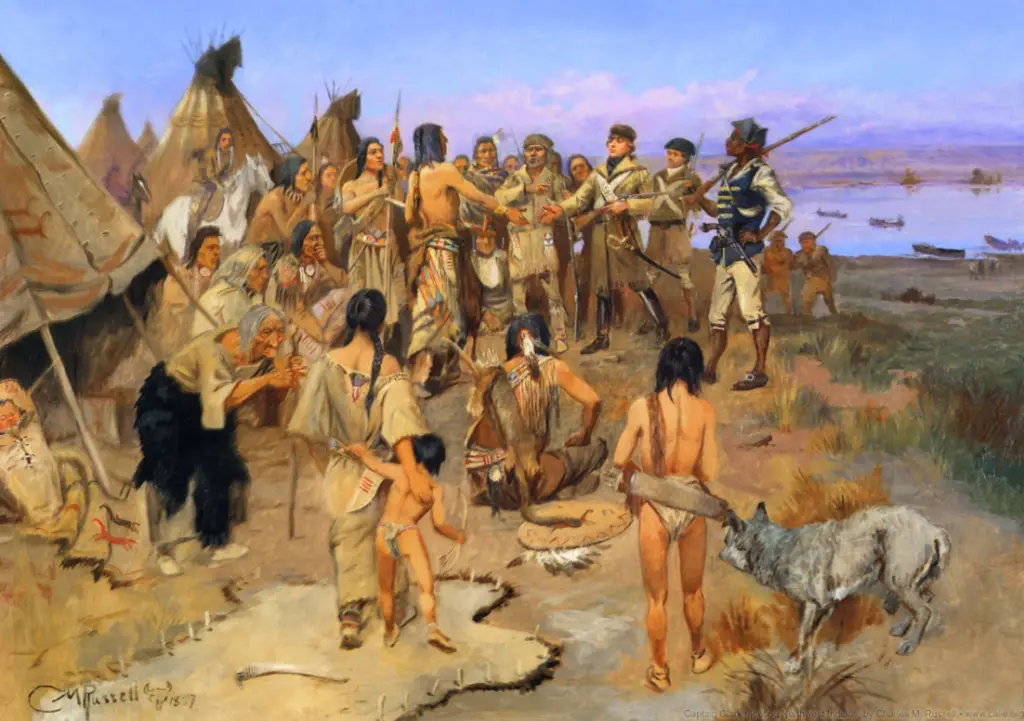

On May 26, 1805, Lewis wrote in his journal that he saw the Rocky Mountains for the first time. He said he felt “joy.” In August, Sacagawea recognized Beaverhead Rock, a place in Idaho where the Shoshone would spend their summers. Days later, Sacagawea had a tearful reunion with her brother, Cameahwait, now a Shoshone chief. (Four years earlier, the Hidatsa raided a Shoshone camp and took Sacagawea prisoner.) Sacagawea persuaded the Shoshone to give Lewis and Clark horses and supplies that would help them get over the Rocky Mountains on their way west to the Pacific Ocean.

Charles M. Russell

In September 1805, the expedition crossed the Rockies with great difficulty. They reached the Pacific Ocean in mid-November and spent a cold, stormy winter near present-day Astoria, Oregon. In March 1806, the Corps of Discovery happily started their return journey home.

Charles M. Russell

Four months later, in July 1806, Lewis and Clark faced the challenge of having to cross over the Rocky Mountains again, this time from west to east. The expedition was in what is now southwest Montana. Sacagawea told Lewis and Clark that she knew the area from her youth and could help them find a different pass back over the mountains. This she did. The Corps of Discovery crossed the mountains at what is now Bozeman Pass.

N. C. Wyeth (Granger Collection)

After crossing the Rockies, Lewis and Clark continued their exploration. They split the group. Lewis took a group to explore the area north of Yellowstone. Clark took the rest of the expedition and explored what is now eastern Montana and western North Dakota. About a month later, the two groups of explorers combined again where the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers meet.

The Corps continued home down the Missouri River. This time they were traveling with the current, not against it. After 8,000 miles, the Lewis and Clark expedition reached St. Louis, the same place they started their journey more than two years earlier.

Wikimedia (March 2021)

Sacagawea was born in the Lemhi River Valley near what is now Salmon, Idaho. She was more than a guide and interpreter. She helped the Native American people they met along the way see that Lewis and Clark meant no harm. (Having a woman and an infant with their group showed the peaceful intent of their mission.) In more ways than one, she helped the Corps of Discovery survive. She helped the expedition make maps of territories that were previously unknown. She did indeed help put America on the map.

Edward S. Paxon

Very interesting! I’d be curious to learn a little more about what happened with Sacagawea after the expedition. Thanks for another awesome read!

Thank you. Great question. While researching for this article, I found two schools of thought on Sacagawea’s death. Some historians cite documents that mention Sacagawea dying in 1812 at the Fort Lisa, a fur trader outpost on the Missouri River in what is now North Dakota. She is said to have died from a fever, probably Typhus. Some Native Americans believe that Sacagawea died much later. Stories passed down in oral tradition suggest that Sacagawea left Charbonneau, made her way back to the Rocky Mountains, and married into a Comanche tribe. The stories say that she returned to the Shoshone people in Wyoming and died in 1884. One grave marker is near Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Sacagawea has another grave marker near Mobridge, South Dakota.

Surely some part of the trail at least ought to be named after her.